Hello ROS community,

as promised in our previous discourse post, we have uploaded our current version of the accelerated memory transport prototype to GitHub, and it is available for testing.

Note on code quality and demo readiness

At this stage, we would consider this to be an early preview. The code is still somewhat rough around the edges, and still needs a thorough cleanup and review. However, all core pieces should be in place, and can be shown working together.

The current demo is an integration test that connects a publisher and a subscriber through Zenoh, and exchanges messages using a demo backend for the native buffers. It will show a detailed trace of the steps being taken.

The test at this point is not a visual demo, and it does not exercise CUDA, Torch or any other more sophisticated flows. We are working on a more integrated demo in parallel, and expect to add those shortly.

Also note that the structure is currently a proposal, detail of which will be discussed in the Accelerated Memory Transport Working Group, so some of the concepts may still change over time.

Getting started

In order to get started, we recommend installing Pixi first for an isolated and reproducible environment:

curl -fsSL https://pixi.sh/install.sh | sh

Then, clone the ros2 meta repo that contains the links to all modified repositories:

git clone https://github.com/nvcyc/ros2.git && cd ros2

Lastly, run the following command to setup the environment, clone the sources, build, and run the primary test to showcase functionality:

pixi run test test_rcl_buffer test_1pub_1sub_demo_to_demo

You can run pixi task list for additional commands available, or simply do pixi shell if you prefer to use colcon directly.

Details on changes

Overview

The rolling-native-buffer branch adds a proof-of-concept native buffer feature to ROS 2, allowing uint8[] message fields (e.g., image data) to be backed by vendor-specific memory (CPU, GPU, etc.) instead of always using std::vector. A new rcl_buffer::Buffer<T> type replaces std::vector for these fields while remaining backward-compatible. Buffer backends are discovered at runtime via pluginlib, and the serialization and middleware layers are extended so that when a publisher and subscriber share a common non-CPU backend, data can be transferred via a lightweight descriptor rather than copying through CPU memory. When backends are incompatible, the system gracefully falls back to standard CPU serialization.

Per package changes

rcl_buffer (new)

Core Buffer<T> container class — a drop-in std::vector<T> replacement backed by a polymorphic BufferImplBase<T> with CpuBufferImpl<T> as the default.

rcl_buffer_backend (new)

Abstract BufferBackend plugin interface that vendors implement to provide custom memory backends (descriptor creation, serialization registration, endpoint lifecycle hooks).

rcl_buffer_backend_registry (new)

Singleton registry using pluginlib to discover and load BufferBackend plugins at runtime.

demo_buffer_backend, demo_buffer, demo_buffer_backend_msgs (new)

A reference demo backend plugin with its buffer implementation and descriptor message, used for testing the plugin system end-to-end.

test_rcl_buffer (new)

Integration tests verifying buffer transfer for both CPU and demo backends.

rosidl_generator_cpp (modified)

Code generator now emits rcl_buffer::Buffer<uint8_t> instead of std::vector<uint8_t> for uint8[] fields.

rosidl_runtime_cpp (modified)

Added trait specializations for Buffer<T> and a dependency on rcl_buffer.

rosidl_typesupport_fastrtps_cpp (modified)

Extended the type support callbacks struct with has_buffer_fields flag and endpoint-aware serialize/deserialize function pointers.

Added buffer_serialization.hpp with global registries for backend descriptor operations and FastCDR serializers, plus template helpers for Buffer serialization.

Updated code generation templates to detect Buffer fields and emit endpoint-aware serialization code.

rmw_zenoh_cpp (modified)

Added buffer_backend_loader module to initialize/shutdown backends during RMW lifecycle.

Extended liveliness key-expressions to advertise each endpoint’s supported backends.

Added graph cache discovery callbacks so buffer-aware publishers and subscribers detect each other dynamically.

Buffer-aware publishers create per-subscriber Zenoh endpoints and check per-endpoint backend compatibility before serialization.

Buffer-aware subscribers create per-publisher Zenoh subscriptions and pass publisher endpoint info into deserialization for correct backend reconstruction.

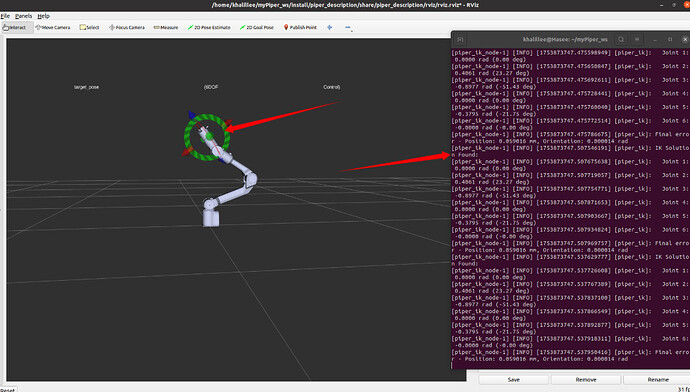

Interpreting the log output

test_1pub_1sub_demo_to_demo produces detailed log outputs, highlighting the steps taken to allow following what is happening when a buffer flows through the native buffer infrastructure.

Below are the key points to watch out for, which also provide good starting points for more detailed exploration of the code.

Note that if you used the Pixi setup above, the code base will have compile_commands.json available everywhere, and code navigation is available seamlessly through your favorite LSP server.

Backend Initialization

Each ROS 2 process discovers and loads buffer backend plugins via pluginlib, then registers their FastCDR serializers.

Discovered 1 buffer backend plugin(s) / Loaded buffer backend plugin: demo

Demo buffer descriptor registered with FastCDR

Buffer-Aware Publisher Creation

The RMW detects at creation time that sensor_msgs::msg::Image contains Buffer fields, and registers a discovery callback to be notified when subscribers appear.

Creating publisher for topic '/test_image' ... has_buffer_fields: '1'

Registered subscriber discovery callback for publisher on topic: '/test_image'

Buffer-Aware Subscriber Creation

The subscription is created in buffer-aware mode — no Zenoh subscriber is created yet; it waits for publisher discovery to create per-publisher endpoints dynamically.

has_buffer_fields: 1, is_buffer_aware: 1

Initialized buffer-aware subscription ... (endpoints created dynamically)

Mutual Discovery

Both sides discover each other through liveliness key-expressions that include backends:demo:version=1.0, confirm backend compatibility, and create per-peer Zenoh endpoints.

Discovered endpoint supports 'demo' backend

Creating endpoint for key='...'

Buffer-Aware Publishing

The publisher serializes the buffer via the demo backend’s descriptor path instead of copying raw bytes, and routes to the per-subscriber endpoint.

Serializing buffer (backend: demo)

Descriptor created: size=192, data_hash=1406612371034480997

Buffer-Aware Deserialization

The subscriber uses endpoint-aware deserialization to reconstruct the buffer from the descriptor, restoring the demo backend implementation.

Deserialized backend_type: 'demo'

from_descriptor() called, size=192 elements, data_hash=1406612371034480997

Application-Level Validation

The subscriber confirms the data arrived through the demo backend path with correct content.

Received message using 'demo' backend - zero-copy path!

Image #1 validation: PASSED (backend: demo, size: 192)

What’s next

The code base will server as a baseline for discussions in the Accelerated Memory Transport Working Group, where the overall concept as well as its details will be discussed and agreed upon.

In parallel, we are working on integrating fully featured CUDA and Torch backends into the system, which will allow for more visually appealing demos, as well as a blueprint for how more realistic vendor backends would be implemented.

rclpy support is another high priority item to integrate, ideally allowing for seamless tensor exchange between C++ and Python nodes.

Lastly, since Zenoh will not become the default middleware for the ROS2 Lyrical release, we will restart efforts to integrate the backend infrastructure into Fast DDS.

2 posts - 2 participants

Read full topic